A long time ago I was in a discussion about process as an “innie” – a User Experience team member that works inside a larger organization, generally whose mission is not to deliver UX to someone else. (An “outie”, on the other hand, works at an agency or as a freelancer to provide these same services.)

The outies I was talking to all believed in small development and design teams who could work quickly and easily, adjust to changes, and provide smooth handoffs. And yes, that works, but it’s not the only way.

Recently, Pamela Drouin mentioned that she’d heard some companies make their UX folks specialize in research or design. Having experienced extreme fragmentation, I threatened to tell her stories of specialization that would terrorize her, and she called my bluff.

So here I give you the most complex and bureaucratic design process I was ever a member of, with the highest level of Design role fragmentation I’ve seen. (For the faint-of-heart, please know this structure has since been dismantled… well, most of it, anyway.)

- Someone gets an idea, which makes it to the business folks with enough authority to decide it’s worth funding.

- The Product Owner writes a Project Charter, passes it through some sort of complex and magical bureaucracy, resulting in a Budget for a Project.

- A Business Lead (responsibilities: translate Business to IT and vice versa, always be available to the dev team for business decisions) is assigned to the project.

- A Business Systems Analyst (BSA) (responsibilities: schedule all the meetings necessary for gathering requirements, gather requirements, facilitate communication with IT) is assigned to the team.

- Depending on the size of the project, the Product Owner, Business Lead, and BSA, along with subject matter experts, market researchers, and other folks, may complete a Business Design Methodology (BDM) project to determine what business problem they’re trying to solve and what approach they want to take.

- When the BDM is complete, a Design Vision is kicked off. Someone contacts the Design Manager (responsibilities: manage a design team, participate in critical projects, set overall organization design strategy) and asks for design resources.

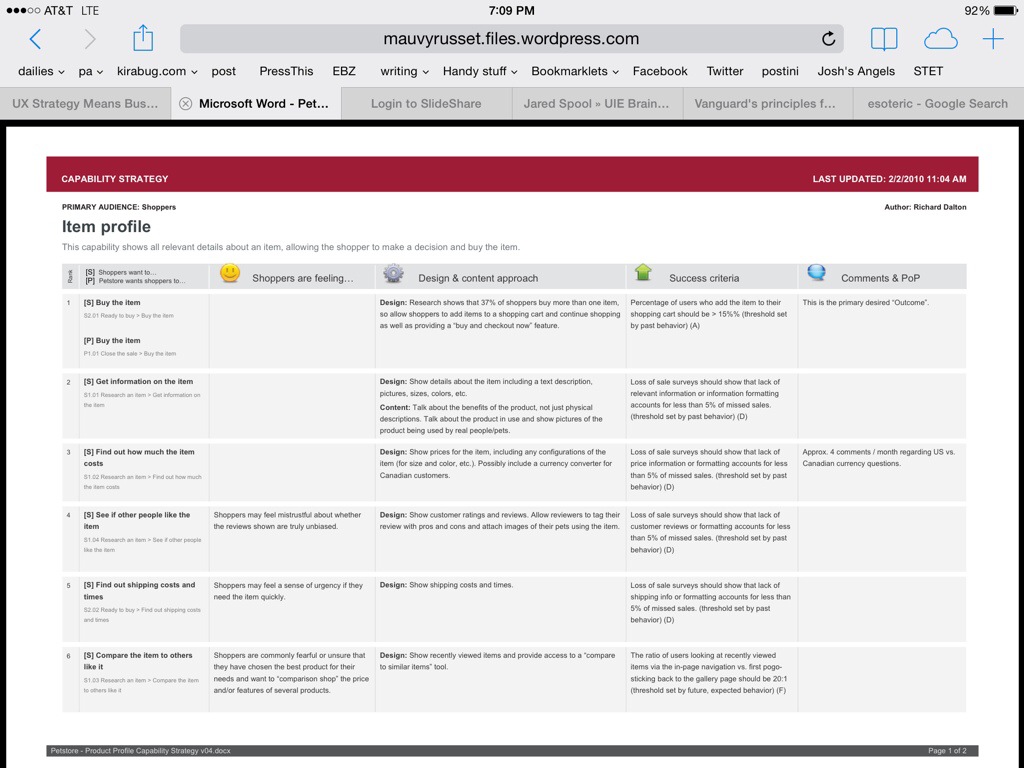

- The assigned Information Architect (IA) (responsibilities: some design research, determining user needs, business goals, structure, navigation, scenarios, site map, strategy, process flows, page flows, alignment with architectural brand standards, and wireframes) meets with the Product Owner and Business Lead, sets a schedule for the Design Vision, and determines what other designers are needed.

- If a BDM wasn’t completed or the BDM didn’t cover enough of the research, a Usability Engineer (responsibilities: user research facilitation, personas, design heuristic analysis, usability testing, design research reports) is immediately engaged; otherwise the Usability Engineer is engaged when wireframes are in progress

- If durable content or news/fresh content is needed, a Content Writer (responsibilities: writing mid-to-long form content, navigating that content through editorial and legal reviews) is engaged.

- A Web Writer (responsibilities: writing all infrastructure content — labels, buttons, instructions, headers, etc. — and ensuring that they’re coded correctly) is engaged.

- An Information Designer (ID) (responsibilities: visual display of the page content, charts, graphs, tables, photography, and illustration, all assets to that effect, ensuring design aligns with visual brand standards) is engaged.

- The IA puts together the Design Vision Plan so that IT knows when they’ll be engaged for development.

- Design Vision meetings occur until the information architecture is stable and wireframes have been developed. All of the people above are required for the meetings in various amounts depending on the day’s topic.

- Sometime during this stage, the Usability Engineer runs initial design heuristic reviews or early usability tests and creates a Usability Report, which the Information Architect dispositions with the team.

- The IA completes the wireframes in Visio and passes them on to the ID.

- The ID “skins” the wireframes in Photoshop.

- The IA, Business Lead, and Product Owner present the current state of the project at an Executive Review. The IA facilitates dispositioning the feedback.

- If a second usability test is needed for interactive elements, the IA engages an Interaction Designer (IXD) (responsibilities: creation of a prototype using HTML, CSS, and Javascript in a test region to capture interactive behavior and assist with usability test) who then builds HTML prototypes, and the Usability Engineer runs another test.

- The Information Architect writes a Design Vision Document outlining all of the design decisions made throughout the Vision including their underlying research, risks, strengths, and which elements of the vision included deep, middling, and shallow analysis. When this is complete, the IA, ID, IXD, Usability Engineer, and probably the Writers are all released from the project.

- Right around this time, an Agile team including a BSA (hopefully the same one), Scrum Master, Tech Lead, developers at the database, mid-tier, and front-end levels, a UCD Designer, Systems Acceptance Test Tester (SAT tester), Client Acceptance Test (CAT Tester) and Web Writer (hopefully the same one) are engaged in Sprint Zero planning. Depending on the number of front-end developers, there may be more than one UCD Designer, because it only takes 3 front-end developers to max out a UCD Designer’s capacity.

- At the end of Sprint Zero and the beginning of Sprint 1, the BSA begins front-running requirements, and the UCD Designer begins front-running designs specific to the Sprint 1 stories.

- From Sprint 1 forward, the UCD Designer (responsibilities: detailed design of all flows, error messaging, prototyping, Page Integrity Test testing (PIT Testing) and facilitation of all design decisions) designs to the detailed requirements, contacting the IA when the detailed requirements conflict with the Design Vision Doc. The UCD Designer also builds a second prototype, this time with component code, determines which parts of the Vision can’t be built using existing component code, and arranges for components to be written or custom code to be delivered for the specific capability.

- During each sprint the UCD Designer works with the Writer to ensure the content is correct and applied, validates testing scenarios and requirements, and documents the Design Specs for the project.

- At least one usability test is required, so the UCD Designer engages (hopefully the same) Usability Engineer. The UCD Designer also participates in the required executive review. The UCD Designer dispositions all the feedback from both reviews with the team.

- During each sprint and again during regression, the UCD Designer PIT tests all visual design elements of the pages or application being changed to ensure alignment with the vision and the Brand Standards.

- After the final set of tests are run, the UCD Designer and the Writer(s) are released from the project. Elevation usually takes place without Design’s participation because if it’s a Design issue at that point, it’s too damn late.

And then it’s done. It only took a Usability Engineer, two kinds of Writers, an Information Architect, an Information Designer, an Interaction Designer, a UCD Designer, and all of the design support roles (design managers, brand managers, marketers, photographers, code component builders, usability test recruiters and schedulers, etc.) to handle the design tasks. Also, approximately seven to twenty other people to do the business and development tasks. Quite probably more when vacations, short-term leave, and job changes are factored in.

In contrast, I’ve also been on teams where, for a given project, we had a business person making the request (but no product owner or business lead), myself playing the role of UX Designer (encompassing IA, Writer, ID, and IXD), a scrum master (who had two other teams), a developer, a BSA who doubled as the SAT and CAT tester, and a Usability Engineer on call when we needed them. Five people on average.

Nobody in their right mind would prefer the super-bureaucratic version of this design process — unless they needed the ability to swap out designers and developers at the drop of the hat, and then redundancy is a very valuable thing.

The risk is that fragmentation of roles and skills can be so incredibly prolific that a “small team” approach to design and development becomes impossible. “Pivoting” from one design or development solution to another also becomes increasingly difficult and expensive.

And yet… that doesn’t mean the software doesn’t ship. Because for every hat the designer takes off, that’s one less piece of work the designer has to do. Fewer roles means less shifting of context, and some efficiency is gained. Some roles, like Writer or Information Designer can be spread across multiple projects, because their skills aren’t needed on a daily basis, and may only be required for a few weeks of a six month or two year project.

The lynchpin is communication. The larger the team, the more time is lost to the overhead of keeping everyone on the same page. On the other hand, the smaller the team, the more skills are lost if one member is a poor communicator, falls ill, or leaves the team. One lousy communicator on a team of four is significantly more dangerous than one lousy communicator on a team of twenty.

Specializing is incredibly valuable if there’s a specific role that a person loves to fill, or a specific role that an organization needs to have handled. I love information architecture and I prefer having as few other roles as possible layered on top of it. As a specialist, I get to spend the vast majority of my time on my favorite tasks and only dip into the others when called upon to do so.

On the other hand, I agree with Jared Spool that compartmentalizing, or only having experience in on area is dangerously unproductive. Even on stupidly large teams and stupidly long projects, an overlap of skills between the different designers (and even the developers and business people) ensures efficiency when someone’s on vacation or away or new.

So to anyone who’s concerned about working for a company that requires specialization, I say don’t worry. Working as a specialist means getting the opportunity to gain a deep understanding of one kind of Design. It means being exposed to specialists in other fields, which makes it it’s a great way to learn a lot without being held responsible for everything. Finally, it means the opportunity to move from one specialty role to another, providing a fresh view of design every few years.

But, y’know, if you can encourage your organization not to specialize to the point of ridiculous, that’s a good idea too.